Good Flaws Connect Readers with Your Hero

Large and Small Hero Flaws

Everyone has flaws, and some are more appealing than others. Flaws and weaknesses keep your hero from being unrelatable. An all-good character isn’t believable. And an unbelievable character keeps your reader from empathizing. If your reader doesn’t empathize, they won’t care. They won’t want to follow your character through 300 pages of the story.

Without flaws, your character is either flat and uninteresting or too good to be true. Either way, you won’t capture reader interest enough to care enough to learn their story.

Flaws and weaknesses in your character allow them to make mistakes and bad choices that lead to a compelling story. A protagonist who never makes mistakes never gets scared and doesn’t misread a situation may end up relying on outside forces to drive the plot. That protagonist ends up reactive, doesn’t lead the story action, and leaves readers cold.

Choose a flaw that fits with the story. If your character cant cook and cooking isn’t part of the story, that flaw doesn’t matter. Your character’s weaknesses drive their mistakes which complicate the story. If the flaw doesn’t fit the story, it will feel forced, and readers won’t care.

But significant dysfunctional flaws will also drive away your reader. Big flaws can drive your story out of the plot. In a mystery, your detective’s crucial role is to solve the puzzle. That challenge takes precedence over any flaw that debilitates your detective’s action. Just like being too perfect, major dysfunction is just too much.

Character flaws make your reader worry about your hero.

Why Balance is Important

You want to keep your reader guessing. Balancing your hero’s redeeming qualities with their weaknesses gives you choices about their next action. It also keeps the reader wondering when the character has to make a choice. At the moment of choice, your character has the potential to make the right decision, but a flaw creates a high possibility for messing up.

Tips for Choosing Flaws

When you understand your character, use their personality to choose flaws that fit their character and the story.

Fears

Fear is a potent motivator and relatable for your reader. They also work in the story because they lead to mistakes, wrong decision, and out-of-character behavior. You’ll have ample opportunity to add conflict.

Fear can be rational, like a fear of snakes, or irrational, like a fear of clowns or dolls.

In a mystery, the fear does not need to be the thing your character must overcome to win—solve the mystery. In fact, when details line up to overcome the fear, your story may feel too perfect by seeming convenient, or worse, coincidental.

Instead, aim for fears that hinder your sleuth in their goal pursuit, create conflict, and cause trouble for your hero.

As you work on your character background, ask questions that reveal fears.

- What past traumas may affect their behavior?

- What irrational fear will hinder normal activity?

- Do they have a secret fear?

- What is their publicly know fear?

- What fears relate to the current problem?

- Is there a fear caused by the plot problem?

- Is there fear drawn from internal conflict?

Once you choose your character’s fears, show them early in the novel, so the reader knows they are a problem. You’re setting up reader questions for situations where the fear can cause failure later in the novel. And, your hero can overcompensate for mistakes made in fear, and make more mistakes.

Personal Prejudice

Cultural and family opinions ingrained since childhood are hard to shake. Your hero’s attitudes and opinions can keep her from clear understanding, especially when your sleuth encounters suspects. Ingrained opinions keep your character from acting in wise ways.

Pre-formed opinions start your character off on the wrong foot. They can misread or mishear suspect statements or form a wrong impression of a victim, leading them to ask the wrong questions of suspects.

Consider your character’s background, culture, family traditions, schooling to create flawed opinions.

- What did they learn to disapprove or dislike as a child?

- What pushes their buttons?

- What actions or beliefs do they believe are wrong?

- What are their intolerances?

- What will they fight for or about?

- What causes them shame?

- What do they believe is bad, even if it is accepted in their current world?

Biases and opinions affect how your sleuth interacts in the world with other people, with settings, and how they perceive the culture around them.

Good Traits

Yes, good traits can transform into flaws. For example, if your hero always does the right thing but is surrounded by people who don’t, he will get blocked. If she is tenacious and encounters a situation that requires she give up to win, she’ll be in trouble.

Force your hero to go against their nature. You’ll add internal conflict to an external goal.

Study your character’s outstanding qualities and then ask:

- What trait symbolizes your character’s soul?

- What positive trait could become a flaw? And in what situation?

- How can a positive trait cause as many problems as it solves?

- What trait annoys other characters?

- What positive trait holds back the character?

Turning good traits into flaws deepens your character and ties your reader to their problem. Your reader already understands their positive traits, and now understands how it led your hero into a problem.

Character Weakness Strengthens Your Story

You build tension for the reader as they wonder how your hero will get out of a critical situation. Flaws and weaknesses lead your character astray—making decisions that lead to additional complications, heading toward a challenge to the weakness, misunderstanding, or misjudging other characters.

Flaws are good for your character and help you create a strong story.

So, what’s a good flaw? A weakness that fits your protagonist’s personality and works in your story plot without overwhelming either the character or the plot.

Love talking about writing mysteries? Join the Mystery Writers Studio.

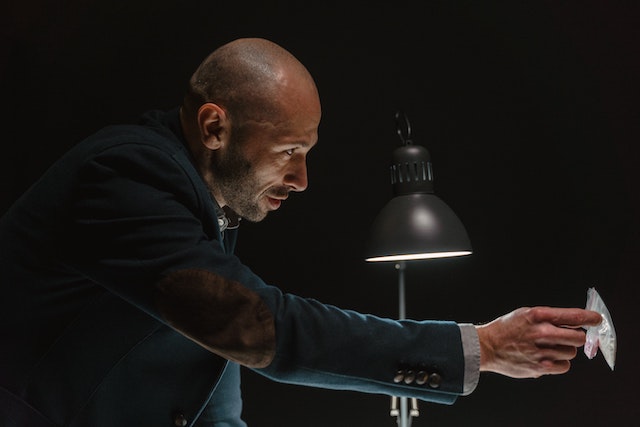

Photo by krakenimages on Unsplash